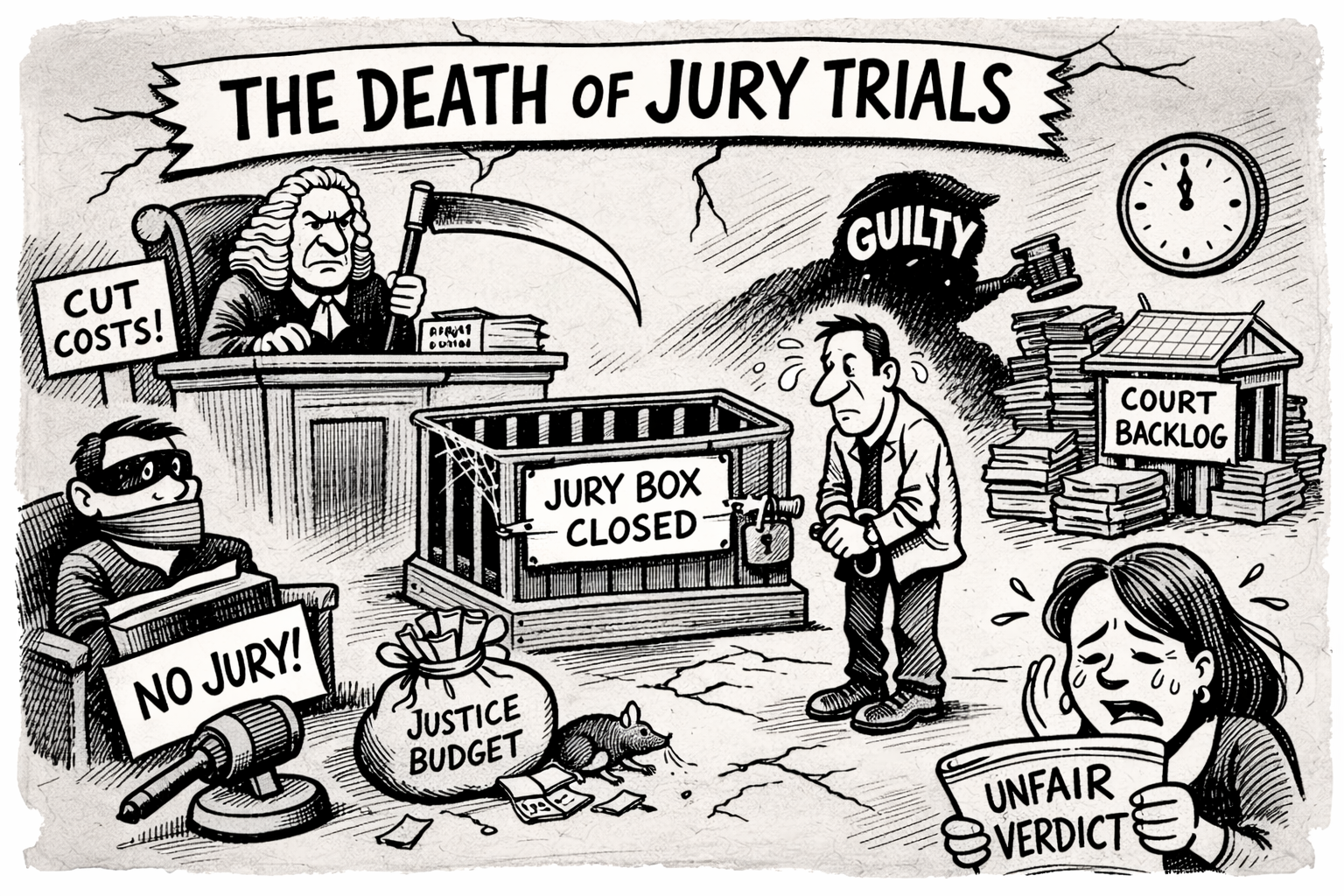

Constitutional protections die, not with a bang, but with a budget cut.

By Meysam Rajaee · Dec 19, 2025

The government has recently proposed to strip away the right to trial by jury. Under the plan, jury trials would be retained only for the most serious offences, murder, rape and manslaughter, while the majority of indictable matters would be tried by a judge sitting alone. The justification is familiar. An intolerable Crown Court backlog, now exceeding 78,000 cases, is said to be the consequence of the inefficiency of jury trials.

For centuries, the right to be judged by one’s peers has formed a central feature of the right to a fair trial. That history, however, is increasingly dismissed. Critics argue that longevity alone cannot justify retention. Capital punishment, after all, was once lawful, it is not so now. The point is superficially attractive. No right should survive merely because it is ancient.

That much is accepted. The case for jury trials should not rest on sentiment or nostalgia. It must be assessed on its function, its consequences, and its constitutional value in a modern justice system. When examined on that basis, the proposal to curtail jury trials is profoundly misguided.

For the right to be judged by one’s peers is not a procedural ornament, nor a quaint historical survival. It is a constitutional safeguard. It restrains the power of the state, demands transparency in the administration of criminal justice, and reminds every participant in the courtroom that justice ultimately belongs not to the judiciary, nor to the executive, but to the public itself.

To remove juries in response to these failures is not reform. It is an attempt to amputate the limb that is not diseased.

A Perspective from abroad: when judges alone decide

For those of us from countries without juries, the stakes are understood differently, and more acutely. I am Iranian by birth. I have seen what judge-only trials can become. In Iran, political cases can last minutes, sometimes no more than thirty seconds. A single judge wields absolute authority over life, liberty, and death, without public oversight or accountability. There is no panel of citizens to ask: Is this fair? Is this right? The process is fast, certainly. But efficiency in such circumstances is terrifying.

Of course, England and Wales are not Iran. No reasonable person suggests it is on a comparable trajectory. But systems do not erode in dramatic collapses, they erode in increments. A small contraction of public involvement here, an expansion of judicial discretion there, and before long the foundations have shifted. You do not appreciate the protection of a jury until it is gone.

Those of us who have seen what happens when judges alone decide must speak plainly: a justice system without juries is not merely thinner. It is weaker, more vulnerable, and more willing to sacrifice fairness on the altar of expediency. And once the right is lost, it will not easily be restored.

A system starved, not broken

The claim that juries are responsible for the crisis in the courts does not withstand even cursory scrutiny. Delays are endemic across the entire justice system. Magistrates’ courts alone face a backlog of approximately 310,000 cases. Family courts are carrying around 110,000 outstanding matters. Employment tribunals remain severely congested. The Social Security and Child Support Tribunal is overwhelmed. The Immigration and Asylum Tribunal has close to 90,000 appeals outstanding. This is not a Crown Court anomaly, it is a system-wide failure.

The present backlog is real, but its causes are well known and long standing. It is not the product of juries. Every part of the administration of justice has been hollowed out by cumulative result of decades of underfunding, insufficient judicial and staff recruitment, transport breakdowns, and a political culture that has repeatedly treated the criminal justice system as an afterthought. The reality is uncomfortable but obvious: like prisons, criminal justice is rarely an electorally attractive investment. Against that backdrop, it is easier to scapegoat juries than to confront the consequences of sustained neglect. Yet juries remain one of the few elements of the criminal justice system that continue to command public confidence.

The irony is stark: of all the resources available to the criminal justice system, the one that is inexhaustible is the public’s willingness to perform jury service. Twelve citizens, ready and able to shoulder a civic duty every Monday morning, yet this is the resource the government proposes to discard.

Unanswered questions

For those with experience of the criminal justice system, the proposal immediately exposes a host of unanswered questions. These are not peripheral concerns, they go to the heart of how justice would function in practice.

We are told that the elimination of juries is a necessary response to an ever-growing backlog in the criminal courts. The argument is framed as pragmatic, even urgent. Yet the same government advancing this proposal announces, without apparent embarrassment, that the changes will not take effect until 2029. One is entitled to ask: what, then, becomes of the intervening years? The backlog continues to swell, cases drift, victims wait for resolution, and defendants languish in prolonged uncertainty.

Will judge-only trials require separate or expanded routes of appeal? If so, any gains in efficiency may be illusory. Will judges be expected to provide detailed written or oral reasons in every case? Transparency may demand it, but such a requirement would inevitably consume judicial time and risk compounding, rather than alleviating delay.

There are also serious practical difficulties in trial management. How are pre-trial legal issues, bad character applications, admissibility disputes, abuse of process arguments, to be handled without overwhelming a single judge who must act simultaneously as arbiter of law and fact? The current system distributes these burdens precisely because of their complexity.

The implications for the prison population have likewise gone unexamined. Conviction rates in the Crown Court are already lower than in the magistrates’ courts. If judge-only trials increase conviction rates, what provision has been made for the resulting rise in custodial sentences? In a system already struggling with overcrowding, this omission is striking.

More fundamentally, the proposal rests on an unexplained moral distinction. How can it be justified that some serious offences “deserve” public adjudication by a jury, while others do not? On what principle does the state decide when a citizen is entitled to be judged by their peers?

Finally, there is the constitutional question. Trial by jury is not a mere procedural option, it is a foundational safeguard of liberty. Should such a profound alteration to the balance between citizen and state not require the explicit consent of the public, perhaps by referendum?

To date, none of these questions has been meaningfully answered. Efficiency is an important aim, but it cannot be pursued at the expense of clarity, legitimacy, and public confidence in the administration of justice. Reform without explanation is not reform at all, it is abdication.

Juries are worth defending

The value of juries lies in far more than constitutional symbolism. What is at stake is the character of justice itself. Juries bring something to the courtroom that no institutional alternative can replicate: a collective judgment formed from the full breadth of society’s lived experience.

Twelve ordinary citizens, selected at random and unknown to one another, carrying perspectives shaped by different backgrounds, occupations, communities, and life histories. This diversity is not simply demographic. It is experiential and intangible, the subtle ways people assess credibility, weigh evidence, and understand fairness. These differences matter precisely because they cannot be standardised or trained into existence.

Judge-only trials, whether conducted by a single judge or supplemented by appointed assessors, inevitably narrow that lens. Even as the judiciary acknowledges its own longstanding diversity deficits, there remains no clear or credible plan for structural change capable of addressing them. Concentrating decision-making power in fewer hands does not correct this imbalance, it compounds it.

Proponents of judge-only trials often respond by emphasising judicial training, professionalism, and independence. But judges, like all human decision-makers, are subject to unconscious bias. Expertise does not eliminate subjectivity, it merely disguises it. Jury deliberation, by contrast, mitigates this risk. Decisions emerge from discussion, challenge, and collective reasoning, ensuring that no single worldview determines the fate of a defendant.

Empirical evidence supports this conclusion. Research consistently shows that judge-only outcomes disproportionately disadvantage minoritised defendants. Group deliberation among jurors reduces the influence of individual bias, while public confidence in the justice system declines when decision-making becomes less representative. Crucially, the Lammy Review found no evidence that jury verdicts are systematically influenced by the ethnicity of defendants.

Beyond the jury debate: systematic erosion of safeguards

Much of the current debate about court delays has fixated on juries. That focus is not only misplaced, it is actively obscuring where some of the most significant changes to the criminal justice system are now taking place. While attention remains fixed on the Crown Court, far-reaching reforms are being introduced quietly and with remarkably little scrutiny in the less visible, and far less glamorous, magistrates’ courts. Several developments, taken together, mark a profound shift in how criminal justice will be delivered. Yet they are rarely discussed as part of a single, coherent picture.

The first is what has disappeared from view. The Leveson proposal for a mixed tribunal of magistrates sitting with a judge, originally floated as a compromise alternative to jury trial, has quietly fallen away. In its place is something far more radical: trial by a single judge sitting alone. This represents a fundamental reconfiguration of criminal adjudication, concentrating fact-finding and verdicts in the hands of one individual. That such a significant departure from long-standing practice has attracted so little public debate should concern anyone who cares about due process.

Alongside this sits the removal of the automatic right to elect trial by jury for offences carrying sentences of three years or less. This is not a technical adjustment. It will redirect a substantial volume of contested cases into the magistrates’ courts, effectively rerouting cases away from juries and into a system already buckling under pressure. The result will not be efficiency, but congestion displaced elsewhere.

In anticipation of that influx, magistrates’ sentencing powers are being expanded yet again, to 18 months’ imprisonment, and in some circumstances up to two years. The direction of travel is unmistakable. We are steadily increasing the punitive reach of magistrates’ courts while simultaneously stripping away the procedural safeguards that historically accompanied serious criminal consequences. More power is being granted, even as scrutiny and protection are reduced.

Most troubling of all is the proposal to remove the automatic right of appeal against conviction from the magistrates’ courts. Under the new framework, defendants would require leave to appeal. This change runs directly contrary to the advice of the Bar Council, APPEAL, and numerous other organisations, all of which have made the same point: there is no evidence of widespread abuse of the existing appeal system. Curtailing appeal rights is not an evidence-based reform. It is a response to institutional pressure and administrative strain.

Viewed together, these changes reveal a clear and consistent pattern. Fewer juries. Fewer safeguards. Fewer routes of challenge. All are justified in the language of efficiency, yet none confront the real causes of delay.

Conclusion

The proposals to curtail the use of juries are not merely misguided. They are dangerous. Juries are not flawless; no safeguard ever is. But they remain the most democratic, diverse, and publicly accountable mechanism we possess for determining guilt in serious criminal cases. They disperse power, counterbalance individual prejudice, and affirm that justice is not solely an act of the state, but an act of society. A justice system that abandons juries does not become more efficient. It becomes more obedient.