Rethinking Pecuniary Loss: Competition Law and "Free" Services in Digital Markets

By Jared · Dec 01, 2025

Introduction

The ongoing collective proceedings in Consumers’ Association (Which?) v Apple Inc raise a novel and increasingly significant question for English competition law in markets built around ostensibly “free” digital services.

In competition cases, English courts have consistently affirmed that a claimant must show a pecuniary form of harm arising from the infringement. As the Supreme Court explained in Sainsbury’s Supermarkets Ltd v Mastercard Incorporated [2020] UKSC 24, damages in competition law are compensatory in nature and are intended to restore the claimant’s position in the counterfactual competitive market.

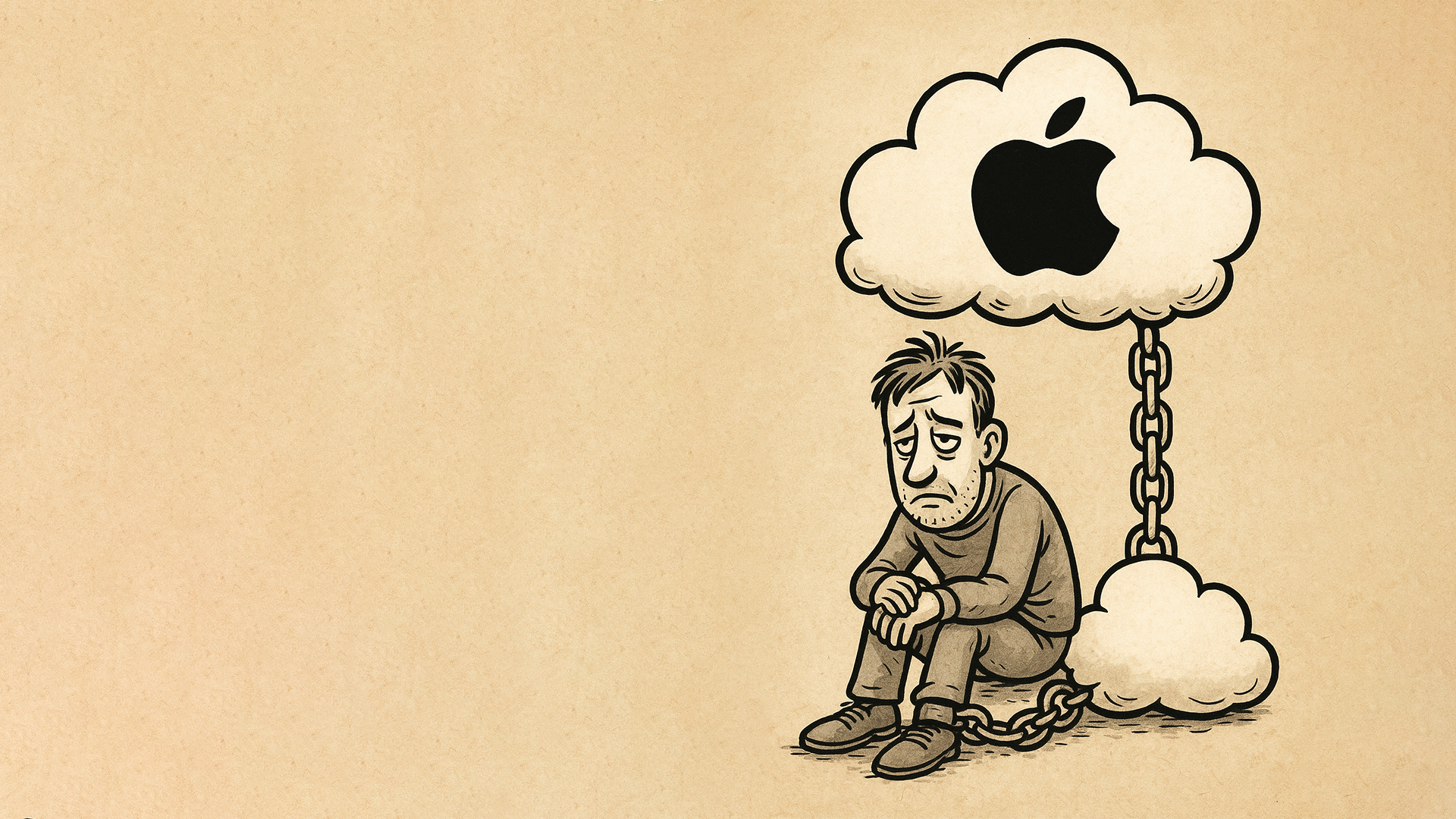

In digital ecosystems where zero-price products are sustained by data extraction, user lock-in, and ecosystem design rather than monetary payment, the orthodox requirement of demonstrable pecuniary loss sits uneasily with the realities of how harm may occur. Apple argues that the absence of expenditure precludes any actionable loss. Which? contends that the economic value embedded in ostensibly free services means that non-paying users are not insulated from competitive detriment. The proceedings thus provide a timely test of whether English competition law’s conception of compensable loss is sufficiently adaptable to reflect welfare effects in contemporary digital markets.

Background

Which? alleges that Apple has engaged in anti-competitive conduct by designing its ecosystem in a way that inhibits the use of rival cloud-storage providers while integrating iCloud seamlessly into its devices, thereby limiting consumer choice and distorting competition in the cloud-storage market. Apple disputes these allegations, arguing that users suffer no disadvantage because Apple devices come with a meaningful allocation of free iCloud storage and consumers remain free to adopt alternative services.

Against this background, Apple has sought to strike out a substantial element of Which?’s claim, namely the claim on behalf of non-paying iCloud users for foregone consumer surplus (FCS), meaning the economic value they would allegedly have obtained in a competitive counterfactual market. Although judgment on this issue is still pending, it raises an important and unresolved point of principle: whether FCS can constitute actionable pecuniary loss under English law.

Apple contended that such loss is inherently hypothetical and grounded in subjective consumer preferences, and therefore falls outside the scope of compensable damage. Which?, by contrast, argued that FCS reflects a real economic detriment capable of legal recognition.

Apple’s Argument: FCS as Speculative and Non-Pecuniary

Apple relies heavily on the Court of Appeal’s decision in BSV Claims Ltd v Bittylicious Ltd [2025] EWCA Civ 661, asserting that the Court definitively rejected novel, economically-constructed heads of loss based on speculative future value. Bittylicious concerned the delisting of a cryptocurrency, BSV. The claimants argued that they had suffered losses as a result, and sought compensation not just for the direct value of their holdings but also for speculative, future gains that they claimed they would have realized had the delisting not occurred. The Court rejected this.

In Bittylicious, the Court emphasised that BSV “was obviously not a unique cryptocurrency without reasonably similar substitutes,” and treated it as a tradable financial instrument rather than special property. On that basis, the Court dismissed the claim based on the so-called “forgone growth effect,” meaning speculative claims that BSV would have appreciated massively had it not been delisted.

Apple argues that the reasoning in Bittylicious applies with equal force to foregone consumer surplus. Like the “forgone growth” theory, FCS rests on hypothetical, counterfactual assumptions about what users might have done or how much they might have been willing to pay in a different market. As such, it is no more than a “preference-based welfare loss,” untethered from actual expenditure, asset diminution, or lost profits, and therefore legally indistinguishable from the speculative losses rejected in Bittylicious. On Apple’s account, FCS should be regarded as non-actionable as a matter of law and struck out at the outset.

Which?’s Argument: FCS as Pecuniary Loss Capable of Valuation

Which? responds that the alleged loss is, in substance, pecuniary because in the counterfactual competitive market consumers would have obtained cloud storage services carrying measurable economic value, either through lower-priced purchases or through an increased allocation of free storage. It argues that willingness to pay, although rooted in individual preferences, is a recognised economic proxy for market value and therefore offers an objective and legally workable method for quantifying the loss.

To support the broader proposition that English law is capable of recognising loss even where it is not reflected in market price, Which? relies on Ruxley Electronics and Construction Ltd v Forsyth [1996] AC 344. There, the House of Lords held that damages may be awarded to compensate a claimant for a “loss of amenity” notwithstanding the absence of any financial diminution.

Which? also cites BritNed Development Ltd v ABB AB [2018] EWHC 2616 (Ch) to show that competition law damages may legitimately incorporate counterfactual economic valuations. In BritNed, the Court accepted expert evidence assessing what the value of the electricity interconnector would have been in an undistorted market and awarded damages reflecting the overcharge caused by the cartel. For Which?, this demonstrates the Courts’ willingness to engage with economic modelling and to compensate for the loss of benefits that would have arisen in a counterfactual competitive environment.

Should FCS be recognised?

On balance, a limited recognition of foregone consumer surplus is defensible and, arguably, necessary to ensure that English competition law reflects the realities of modern digital markets. While Apple correctly emphasises that FCS is hypothetical and relies on counterfactual assumptions, the comparison to Bittylicious is imperfect, not merely due to the distinction between cryptocurrency markets and cloud storage, but also due to Apple’s dominant market position.

Which?’s arguments demonstrate that FCS can, in principle, be quantified using established economic proxies such as willingness to pay, and that English law has previously recognised non-pecuniary losses in Ruxley and counterfactual economic valuations in BritNed. Properly constrained by rigorous evidential standards, limits on speculation, and a requirement of demonstrable economic value, FCS can thus operate as a principled extension of compensable loss rather than a radical departure. This approach reconciles Apple’s concern over indeterminate, purely welfare-based claims with Which?’s demonstration of measurable consumer detriment, ensuring that competition law remains capable of addressing anti-competitive conduct in digital markets without sacrificing doctrinal coherence.

Jared Higgins